I've Been To See The Elephant

STEVE BURNS

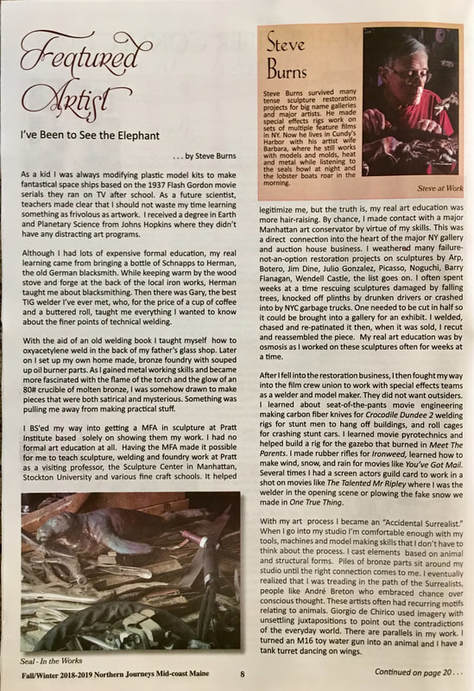

As a kid I was always modifying plastic model kits to make fantastical space ships based on the 1937 Flash Gordon movie serials they ran on tv after school. As a future scientist, teachers made clear that I should not waste my time learning something as frivolous as artwork. I received a degree in Earth and Planetary Science, from Johns Hopkins where they didn’t have any distracting art programs.

Although I had lots of expensive formal education, my real learning came from bringing a bottle of Schnapps to Herman, the old German blacksmith. While keeping warm by the wood stove and forge at the back of the local iron works, Herman taught me about blacksmithing. Then there was Gary, the best TIG weldor I’ve ever met, who, for the price of a cup of coffee and a buttered roll, taught me everything I wanted to know about the finer points of technical welding.

With the aid of an old welding book I taught myself how to oxyacetylene weld in the back of my father’s glass shop. Later on I set up my own home made, bronze foundry with souped up oil burner parts. As I gained metal working skills and became more fascinated with the flame of the torch and the glow of an 80# crucible of molten bronze, I was somehow drawn to make pieces that were both satirical and mysterious. Something was pulling me away from making practical stuff.

I BSed my way into getting a MFA in sculpture at Pratt Institute based solely on showing them my work. I had no formal art education at all. Having the MFA made it possible for me to teach sculpture, welding and foundry work at Pratt as a visiting professor, the Sculpture Center in Manhattan, Stockton University and various fine craft schools. It helped legitimize me, but the truth is, my real art education was more hair-raising. By chance, I made contact with a major Manhattan art conservator by virtue of my skills. This was a direct connection into the heart of the major NY gallery and auction house business. I weathered many failure-not-an-option restoration projects on sculptures by Arp, Botero, Jim Dine, Julio Gonzales, Picasso, Noguchi, Barry Flanagan, Wendell Castle, the list goes on. I often spent weeks at a time rescuing sculptures damaged by falling trees, knocked off plinths by drunken drivers or crashed into by NYC garbage trucks. One needed to be cut in half so it could be brought into a gallery for an exhibit. I welded, chased and repatinated it then, when it was sold, recut and reassembled the piece. My real art education was by osmosis as I worked on these sculptures often for weeks at a time.

After I fell into the restoration business, I then fought my way into the film crew union to work with special effects teams as a welder and model maker. They did not want outsiders. I learned about seat-of-the-pants movie engineering making carbon fiber knives for Crocodile Dundee 2, welding rigs for stunt men to hang off buildings, and roll cages for crashing stunt cars. I learned movie pyrotechnics and helped build a rig for the gazebo that burned in Meet The Parents. I made rubber rifles for Ironweed, learned how to make wind, snow, and rain for movies like You’ve Got Mail. Several times I had a screen actors guild card to work in a shot on movies like Talented Mr Ripley where I was the welder in the opening scene or plowing the fake snow we made in One True Thing.

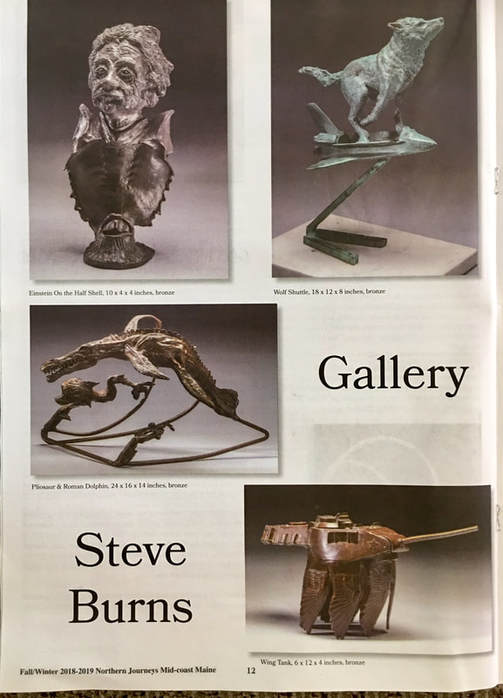

With my art process I became an “Accidental Surrealist.” When I go into my studio I’m comfortable enough with my tools, machines and model making skills that I don’t have to think about the process. I cast elements based on animal and structural forms. Piles of bronze parts sit around my studio until the right connection comes to me. I eventually realized that I was treading in the path of the Surrealists, people like André Breton who embraced chance over conscious thought. These artists often had recurring motifs relating to animals. Giorgio de Chirico used imagery with unsettling juxtapositions to point out the contradictions of the everyday world. There are parallels in my work. I turned an M16 toy, water gun into an animal and I have a tank turret dancing on wings. What if a surviving Plesiosaur was swimming in the deep ocean with a dolphin from Roman mythology? What if animals were riding on space shuttles (cast from a plastic model) to be free on their own planet? What if endangered species were armed and armored to defend themselves like Goodbye Kitty?

You don’t have to go to art school to appreciate my work. Kids relate to my sculpture, and, of course, want to play with it. I created two Art In Public Places sculptures in New York State that were embraced by the local people. One, on the Ramapo River, tells the history of an old iron bridge. It included a may fly, a trout, a period correct locomotive and memorializes a large buck that lived nearby. The locals like it well enough to put a red nose on the buck every Christmas. I’m honored that a local town chose me to work with a piece of steel from the wreckage of the Trade Towers to make a memorial to the local firefighters that died on 911.

I feel successful having come up with ways to bring my welding and sculpture skills into the real world. I made a living doing heavy equipment repairs, special effects and restoration work. I made a difference teaching recent immigrants welding skills that enabled them to get good jobs and improve their lives. Some of my best students were motivated and capable women. A few went on to make a living welding professionally and others went on to become blacksmiths and sculptors.

Steve Burns’ work can be seen at Markings Gallery in Bath, ME. He and his wife Barbara, a tapestry artist live full time in Cundy’s Harbor, ME www.BurnsSculpture.com